An Easy Experiment To Try

It would be natural to read these posts and wonder why I’m so passionate about intonation, and why I’m going to so much trouble to explore it in this blog and in real life. After all, we’re talking about tiny differences in tuning here, why be so picky when it’s the heart that counts?

It’s true, the tuning differences are small, and hard to hear. Thing is, it’s not actually about the pitch. It’s about the way it feels, and in that realm, the difference is not subtle at all. It is profound, and once you hear (no, feel) it, I think you may be hooked, or at least understand more of why I’m so interested in this subject. I think it opens the door to music that truly moves both the performer and the listener, a recipe for audio joy. You bet it’s about the heart. This is not just an intellectual pursuit.

Here is an experiment you can do, to feel that difference in yourself. It uses a chord, and a melody, that you probably already know.

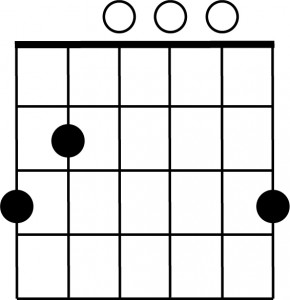

The open G chord is one of the most common chords in guitar music. It looks like this:

The notes, from left to right, are: G–B–D–G–B–G. If G is the tonic, these notes are the 1, 3, 5, 1, 3 and 1.

One of the best-known melodies in the world is Frère Jacques, or in English, Are You Sleeping (Brother John), a round that is hundreds of years old. It could be harmonized in several ways, but the melody is such that it sounds fine sung over just the tonic chord, over and over again.

Here’s the experiment. First, tune your guitar carefully. A tuner is best. When the open strings are in tune, double check the notes of the open G chord. I think Jody showed me this — it often sounds better if you tune to the tonic chord of the song instead of to the open strings.

Now play a full, open G chord as above. Make sure all the strings sound clearly. You are playing a chord with an unusual property: It has two equal-tempered major thirds in it. This chord is highly equal-tempered in character.

Strum away, and sing Frère Jacques over it, several times through. You may wish to capo and tune again, if this is not a comfortable key for you.

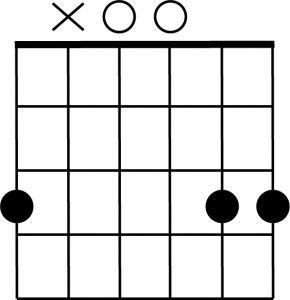

When you have a good sense of what this feels like, try fingering the G chord as follows:

I’m a thumb-wrapper, so I finger the low G with my thumb, and mute the A string with more of my thumb. (This is heretical to some, but it’s a wonderfully useful technique when used at the right time. Here’s a beautiful explanation by guitar teacher Jim Bowley.) Then I finger the two high notes with my index. Any fingering will work as long as it mutes the A string.

Now you have a chord with no major thirds at all. It goes G—D–G–D–G, or 1—5–1–5–1.

Sing Frère Jacques over this chord, several times through and check out what happens.

I won’t tell you what to feel. Don’t worry about trying to hear or sing subtle tuning differences. Just pay attention to your singing, and to your body’s reaction.

Seriously, go do this now, or the next time you’re near a guitar. It works great with piano too, and in any key. First play a major chord, with a couple of thirds in it to really make the point. Then play only roots and fifths. Sing the song over each version of the chord, back and forth. The difference may surprise you.

I’ll check in tomorrow with my own conclusions.

Next: More Experimenting