The Untempered Major Scale

In harmonic space, the clearest name for each note is its ratio — 5/3, 3/2, 4/3, etc. Precise and unambiguous. But the ratios don’t give a very good idea of how to go about playing or singing those notes.

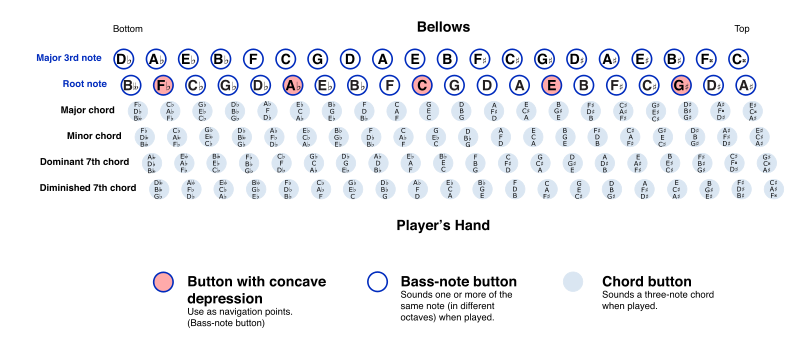

There are a few instruments, such as the left hand keyboard on the accordion, that are organized for harmonic thinking.

The rows are arranged in fifths, and the first two rows are a major third apart, just like the lattice.

For most music making, though, we need to know the pitch of the note. Instruments and voices tend to live in the world of melodic space — scales and pitches.

Here’s what the simplest, most harmonically consonant major scale looks like on the lattice:

One can convert the ratios to pitches using the formula for cents. The ET values are in parentheses.

1 = 1/1 = 0 cents (0)

2 = 9/8 = 204 (200)

3 = 5/4 = 386 (400)

4 = 4/3 = 498 (500)

5 = 3/2 = 702 (700)

6 = 5/3 = 884 (900)

7 = 15/8 = 1088 (1100)

Note that the 1, 2, 4 and 5 are very close to their ET equivalents. Most ears would be unable to tell the difference.

The third, sixth and seventh, however, are all noticeably flat. Or perhaps I should say their ET namesakes are noticeably sharp.

I think this explains a lot about rock music, which depends heavily on power chords (roots and fifths with no thirds) and 1-4-5 chord progressions. The notes of a 1-4-5 power chord progression are 1, 4, 5 and 2!

As Eddie Van Halen said in his terrific Guitar Magazine interview, “Really, the best songs are still based on I-IV-V, which is so pleasing to the ear. Billy Gibbons [of ZZ Top] calls me now and then, and he always asks, ‘Eddie, have you found that fourth chord yet?’ [Laughs].”

Of course the I-IV-V is inherently satisfying, it’s that great rocking chair between reciprocal and overtonal territory, in the most consonant part of the lattice, as close to the tonic as you can get (harmonically).

But I think the special appeal for rock music is that, in ET (and guitar is essentially an equal-tempered instrument), the 1, 4 and 5, and also the fifth of the 5 (the 2) are all in tune. Whatever one might think of ZZ Top’s simplicity (and some do scoff), it’s undeniable that they are fiercely in tune, and harmonically their music strikes a deep chord in the psyche, pun intended.

If the bass and rhythm guitar stick to those roots and fifths, the voices and lead guitar can play all the other notes, because they can be bent and wiggled until they sound right.

This works just as well in traditional country music. Let the bass player nail down those roots and fifths, and the voices (and the fiddle) can sing in-tune harmonies as sweet as you please.

Next: The Major Scale in Cents