Rosetta Stone

Almost all Western music, including my own, lives in the world of tonal harmony. This means:

- There can be, and usually are, multiple notes playing at the same time.

- There is a key center, or tonic, around which the notes are arranged. The tonic doesn’t always sound — it’s an intangible presence, the home from which you leave on your harmonic journey, and to which you will hopefully return.

The multiple notes can have different functions:

- Roots are the fundamental notes of chords. A G chord has its root on G. Roots are local centers that move the ear around the lattice as they change.

- Harmonies flesh out the chord. In a G major chord, the harmony notes are B and D. They stake out more lattice territory and add definition to the chord. Is it a G major, minor, seventh? The harmonies establish this.

- Melodies dance in the harmonic field set up by the tonic, roots and harmonies. They have more freedom than the others. Melodies travel fast and light, and though they can sing the same notes as the others, they can also travel farther afield, further embellishing the chord, or leading the ear toward the next chord in the progression, or lingering on the last one after it has changed.

All this action is happening in two musical spaces at once.

Melodic space is the world of scales. It’s organized in order of pitch. The piano keyboard is a perfect representation of melodic space.

Harmonic space is the world of ratios. Multiply a note by a small whole number ratio, and you have moved a small distance in harmonic space. Multiply by large numbers, and you have moved a large distance. The lattice is a map of harmonic space.

The two worlds are not the same. Often, they are opposites. The perfect fifth is a small move harmonically but it’s a mile in the melody — bass singers have to jump all over the place in pitch. Small melodic moves tend to be big harmonic ones. A chromatic half step, the distance between the 3 and b3, is only 70 cents, less than the distance between neighboring keys on the piano. But on the lattice, it’s a long haul — down a third, down another third, and up a fifth.

Writing and arranging a song is sort of like designing (rather than solving) a crossword puzzle. There are two intersecting, independent universes, Up and Down. To design the puzzle, you work back and forth between the two, massaging them until they don’t conflict, and each one makes sense on its own.

All of the notes live in both harmonic and melodic space. They may have a foot in one more than the other — the roots tend to move small distances on the lattice, the melodies usually move small distances in pitch, and the harmonies tend to bridge the two, moving melodically while staking out the form of the music on the lattice. But every note moves in both spaces, all the time.

A great advantage of the lattice is that it serves as a sort of Rosetta Stone, a bridge or translator between the two worlds.

A great advantage of the lattice is that it serves as a sort of Rosetta Stone, a bridge or translator between the two worlds.

The Rosetta Stone was carved in 196 BC and rediscovered in 1799. It immediately became famous because it repeats the same text three times, in three different languages. It was the key that allowed scholars to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The lattice bridges the two musical spaces by means of the patterns it presents to the eye.

When two or more notes are plotted on the lattice, they will form a particular visual pattern. Any time you see this pattern, no matter where on the lattice it is, the relationship between the notes of the pattern will be exactly the same, in both harmonic and melodic space.

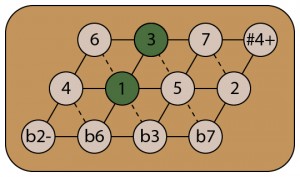

For example, this pattern shows an interval of a major third. The ratio of the frequencies of these two notes is 5/4 (or 5/2, or 5/1 — twos don’t count, they just shift the note by an octave). Any time you see two notes in this formation, no matter where they are, you know they have the following relationship to each other:

For example, this pattern shows an interval of a major third. The ratio of the frequencies of these two notes is 5/4 (or 5/2, or 5/1 — twos don’t count, they just shift the note by an octave). Any time you see two notes in this formation, no matter where they are, you know they have the following relationship to each other:

- Harmonic space: When the notes are sounded simultaneously, they will have the characteristic sound of a pure major third.

- Melodic space: When you move from one note to the other, you are traveling a distance of 386 cents, or about four semitones on the piano.

Getting familiar with these patterns, and learning to recognize them wherever they are, has made it easier for me to think in harmonic and melodic space at the same time, which makes writing and arranging music much easier.

Next: Tonal Gravity